Do you want to learn more about mouse models in ME/CFS?

The first animal models for ME/CFS are underway!

We are creating a mouse model for each of the major symptoms in ME/CFS:

In case you missed it:

Dr. Dada Pisconti PhD talks mouse models at the IACFS/ME Conference in July

The Importance of Mouse Models

One of the major reasons ME/CFS has virtually no treatment trials is due to the lack of animal models. Animal models create a simple, cost effective tool for scientists and pharmaceutical companies.

At the IACFS/ME Conference, Dr. Pisconti from SUNY Stony Brook led a timely workshop about the need for disease-specific animal models for ME, and we wanted to share her insights as background for the work Simmaron is doing to fill this gap.

She outlined the roles animal models play in medical research:

conducting experiments that can’t be performed on humans

controlling factors that affect experiments

reducing placebo effect

obtaining an array of objective outcome measures

Those are important roles in learning about disease processes and treatments.

Critique for the "fatigue" mouse models that have been used thus far

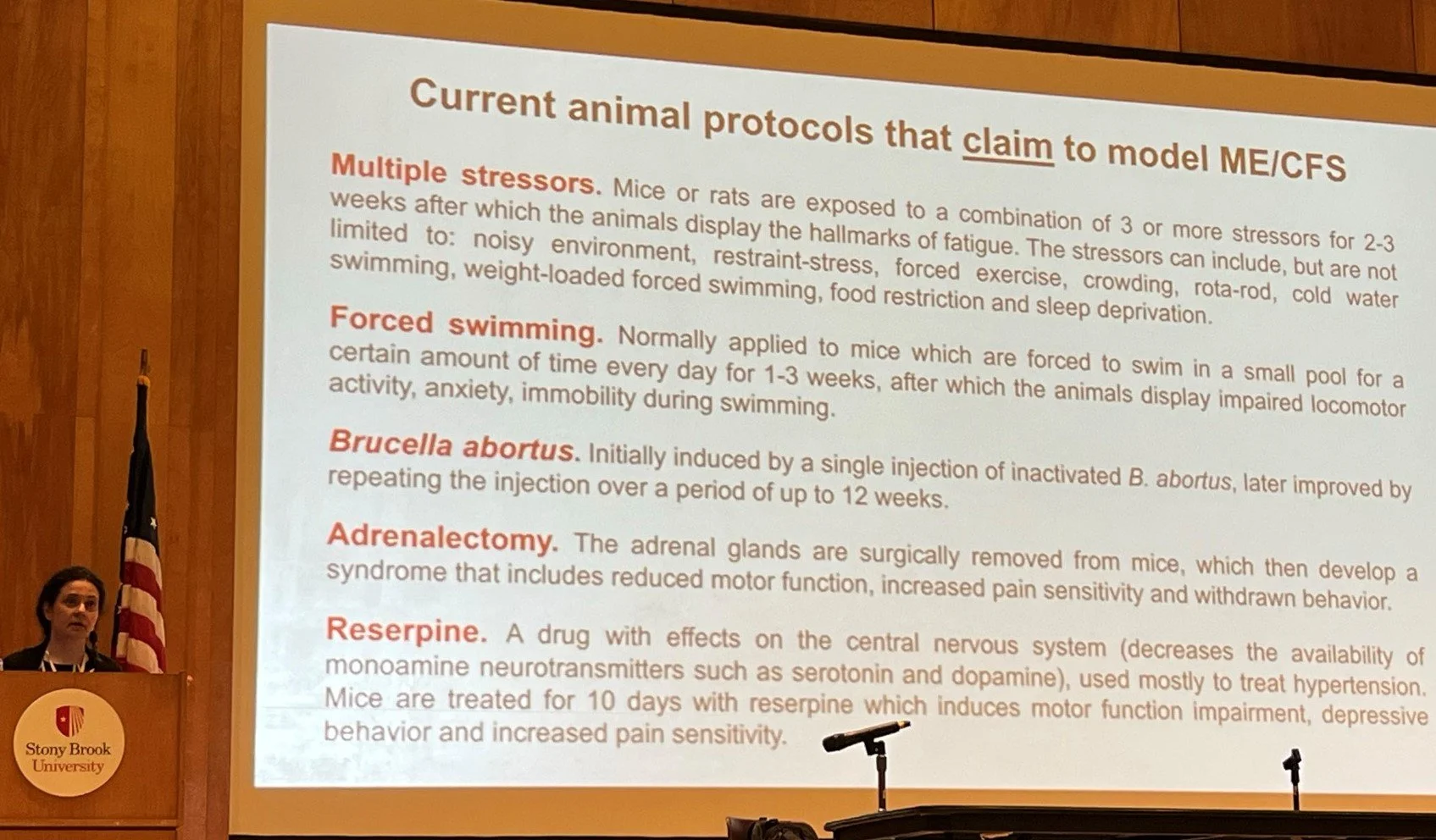

Dr. Pisconti described proxies that are being used in ME/CFS research and then analyzed their shortcomings.

She said one set of animal models used to approximate ME/CFS is created through stressors, such as: forced exercise; combining stressors to induce fatigue; infection with Brucella; adrenalectomy; and use of reserpine, a central nervous system drug that induces depressive behavior, reduced motor function and increased pain.

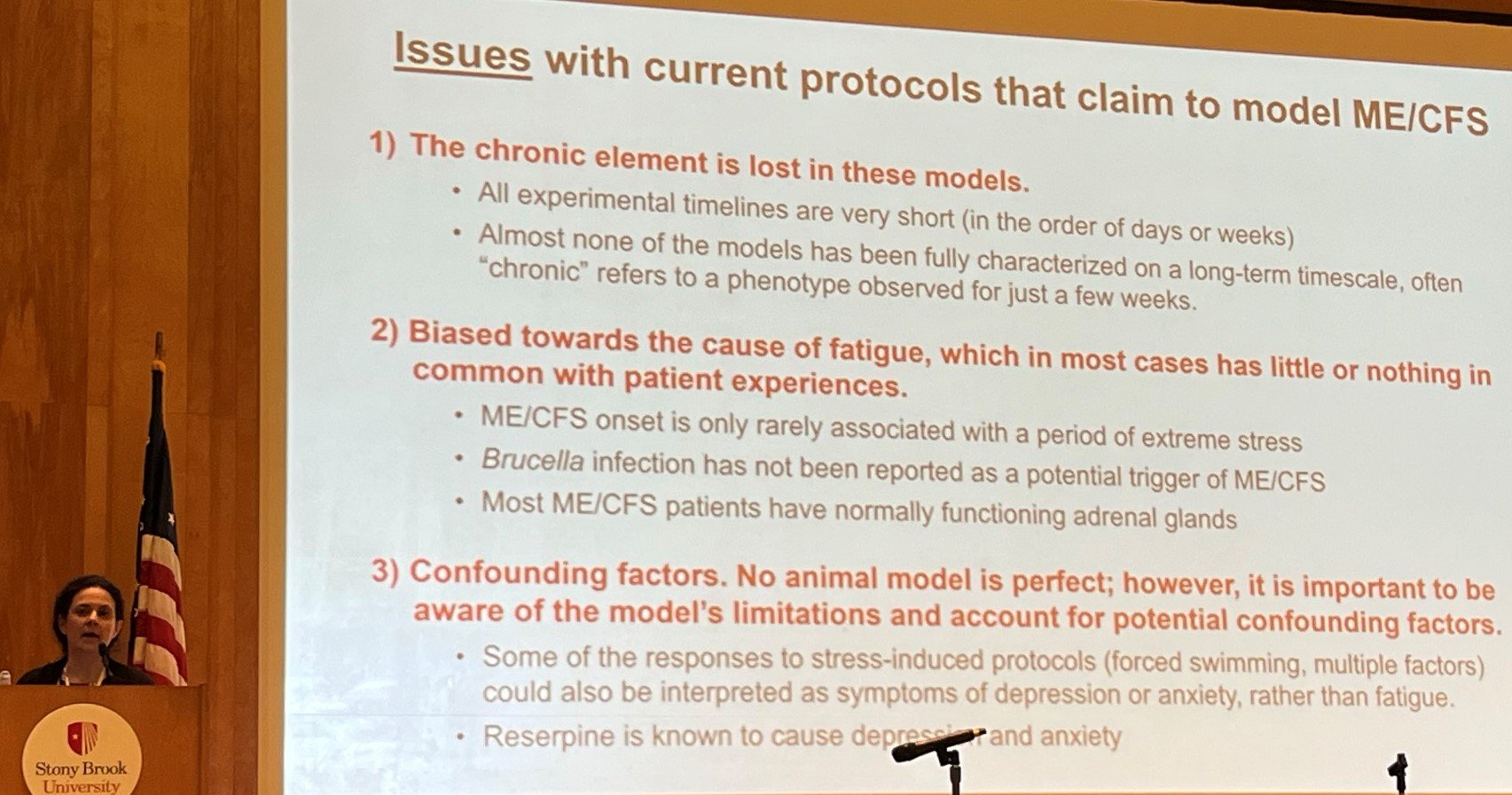

Chief among Dr. Pisconti’s critiques is that conditions induced in these animal models are not chronic, and they are caused by stressors that have little in common with triggers of ME/CFS.

Moving from "Fatigue" to true PEM

Dr. Pisconti also describes animal models based on other diseases as potentially valuable fatigue models, under the hypothesis that if multiple models of fatigue can identify a common molecular signature of fatigue, they could be valuable to help manage that symptom in ME/CFS. Examples given were: Gulf War Illness model, infection-induced model, cancer-induced, autoimmune disorders, sleep-deprived and inflammation-induced models.

But these are not animal models of ME/CFS, she notes.

Dr. Pisconti sees the need to “use existing knowledge to generate new animal models” of ME/CFS, and we are excited that she highlighted Simmaron’s new mouse model, saying it “... is currently being characterized and may soon become a valuable tool.”

Because mouse models can attract pharma research, we are working as fast as we can with experts in animal modeling at the Milwaukee Institute for Drug Discovery at University of Wisconsin Milwaukee.

You can read more details about Simmaron’s mouse model work in our Summer Update here, and follow our progress in the coming year.